I’ve been meaning to write this post for a long time. 2012 was the 40th anniversary of the destruction of the Pruitt-Igoe housing development in St Louis, Missouri – one of the most iconic public housing ventures of all time; March 2013 marks the 41st anniversary. The land where the buildings stood is still vacant, with a fence around it; 57 acres of urban wilderness in the most literal sense.

In recent years, the site has received a lot of attention – most notably, in the form of Pruitt Igoe Now, a documentary released in 2011. A design competition, soliciting suggestions for what to do with the site, was conducted in 2012 – the winning submissions are viewable on the website; predictably, many focused on urban ag or forestry, though the diversity achieved within the theme is pretty impressive. And the mostly-excellent design podcast 99% Invisible did a piece on Pruitt Igoe for their 44th episode, though most of their content was derived from the film.

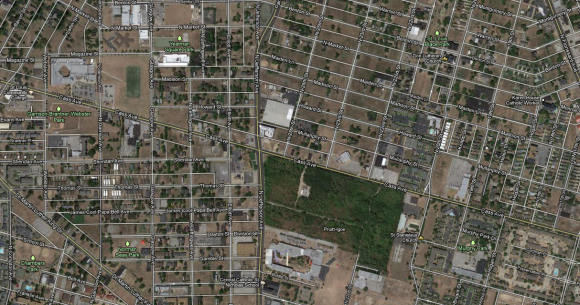

Image courtesy Pruitt Igoe Now design competition – from ‘Connections,’ a finalist in the competition

There are obviously all sorts of reasons why the housing project failed, and architecture is part of it – similar towers have failed elsewhere; Pruitt Igoe is simply the most iconic. But the film works hard to couch the development’s demise in the larger context of post-war St. Louis, and if you look at the image above, you can get a sense of the devastation experienced by adjacent areas that weren’t leveled. By my count, the twenty blocks north of the development have twenty houses on them. It is easy to fetishize Pruitt Igoe, but doing so completely ignores the huge swathes of adjacent land that are almost as devastated – and they didn’t have a huge, iconic explosion to help them get that way.

What is to be done with cities like St. Louis, where large chunks of the urban area are essentially ghost towns? Suggestions that the area be allowed to return to nature, that the remaining citizens be relocated, is typically not politically achievable. On the other hand, neither is it economically feasible to provide urban services to places that have one home per city block, usually with diminishing tax revenue. In New Orleans, the post-Katrina ‘green dot’ map of unviable neighbourhoods provoked a shitstorm of protest from local residents, who in many cases rebuilt with a vengeance in places that should never have been built on in the first place – but that’s a rant for another time. I’ve written before about neighbourhoods on the cusp, like the Near North Side of Pittsburgh, and I won’t rehash that post anymore here. Whatever solutions we do come up with for shrinking cities, the testing grounds shouldn’t be limited to the Pruitt Igoe site; while it is absolutely a good idea to invest in the large scale ecological regeneration of St. Louis, and there is symbolic value to starting with the Pruitt Igoe site, it’s now a 40 year old urban forest and it has value unto itself. Its not like there’s no other land to work with; maybe just leave well enough alone until such time, if ever, when there’s a reason to redevelop.

And in the meantime, check out the film, podcast, Economist article, MIT studio, and book chapter on St Louis in particular and shrinking cities in general. If you have resources or thoughts on Pruitt Igoe, St. Louis or shrinking cities, please let me know.