The planning world is (moderately) abuzz lately with news that LA and New York have been ticketing pedestrians for unsafe walking in an attempt to cut down on car-walker conflicts.

While this has generated at least three news articles that I have seen, it has not generated the response that I feel the whole thing deserves. I don’t think there should be outrage or hysteria or even sadness, but mockery: ticketing pedestrians for walking are ludicrous, and has not been treated with the derision it deserves. It is also reminiscent of a recent traffic safety campaign in London where cyclists and motorists – but really, mostly cyclists – were lectured by police stations around the city (and in some cases fined) for unsafe behavior. This isn’t because walkers or bikers are inherently behaving more dangerously, but because they move more slowly and can hear more clearly when police yell at them.

The most depressing thing is that it seems like, in both cities, ticketing pedestrians stems from a sincere effort to reduce injuries. In doing so, however, it assumes that pedestrians are to blame for car-on-walker conflicts, and it also assumes that people crossing the streets cannot be trusted to act responsibly and with an iota of common sense. In fact, most pedestrian traffic injuries occur at intersections when cars are trying to turn into pedestrians’ right-of-way.

My father (who recently called me a proto-fascist for my views on smoking), taught me that there is a clear hierarchy in terms of street priority: people before machines. Practically, this means that pedestrians come first, then cyclists, then I suppose buses. The easiest take-away is this: cars come last. Cars always come last. While this was a credo that he embraced much more firmly after he started cycling, it is also an easy, simple mantra that guided my notion of good placemaking. In big cities, the large numbers of pedestrians – who, let’s not forget, also constitute traffic – should be welcomed; they are a sign that the city is a good place to be. Instead, they are cited as obstructions to auto traffic and confined to narrow sidewalks.

Its a truism in planing that people will follow the shortest route between two places. They don’t like long, scenic walks between crosswalks; if jaywalking is the easiest way to get from point A to point B, that is what they will be inclined to do. And that’s a good thing. Because a lot of what pedestrians do in cities is spend money: when I lived in Madison, Wisconsin, I lived on State Street, the city’s most famous commercial (and largely pedestrianised) thoroughfare. And thank goodness I had a bike. Because on the rare occasion that I walked, I spent money: I would rent a movie (because this was in the heady early days of streaming video, back when video rentals existed), or buy an ice cream cone or a bubble tea or some other ridiculous thing that I absolutely did not need. And then I’d walk down the street in the evening summer sun, thinking about how great State Street was and wishing I was old enough to get into bars (not necessarily in that order). WalkBoston, an advocacy group in Massachusetts, have crafted their whole mission around that idea: people on foot are better for the economy that people traveling by any other means, because of their tendency to spontaneously spend money

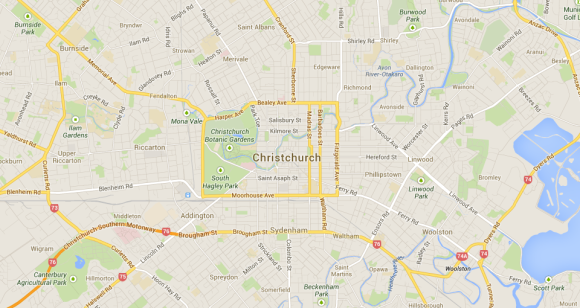

Cities have an obligation to make their streets as safe as possible for as many people as possible – I think most people agree that public safety is one of the functions of municipal government. And there are all sorts of ways to do that without tickets, for anyone. As many others have pointed out, the best way to reduce rule-breaking is to make rules that work better for people. That could mean installing mid-block crosswalks, making traffic crossing times longer, or installing more ‘all green scrambles’ where all car traffic is held at a corner and walkers can cross diagonally, all of which are compromise options (I haven’t even mentioned woonerfs yet!). People have a right to use their own streets, the same way cyclists and cars do. The notion that cars have some god-given priority is laughable, or would be if it didn’t seem to govern city policy all over the world. When that happens, the whole thing just becomes depressing.